Esperanto

Esperanto

Esperanto Support Group

Convenors: Chris Murray chris.murray@esperanto.ie John Murray john.murray@esperanto.ie

Esperanto is an international language designed to be relatively easy to learn, fascinatingly flexible to use and offering a neutral hopeful method of communicating across the world’s cultures. Every Esperanto speaker uses it as a second language. Nobody starts off with the built-in advantage of being a native speaker. Most users are inspired by the ideal of fairness behind the language. Esperanto looks and sounds like as a southern European language (such as Italian), but it is actually built out of ‘unchanging blocks’ like Lego. This makes its structure more like in Hungarian or some Asian languages, and so in a way more ’international’.

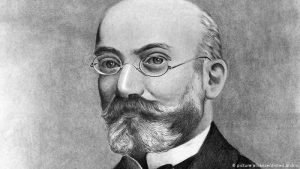

Esperanto probably has only hundreds of thousands rather than millions of active users. Nobody really knows. Speakers are to be found in most countries across the world, so the Esperanto community is a unique diaspora. One determined gifted individual, Lejzer Zamenhof (above), spent years designing the language, but then on publication day renounced all rights to personal ownership. So ever since, Esperanto has developed just like a ‘normal’ language. It depends on how creatively people use it! Today, well into its second century of life, Esperanto already has a remarkably extensive library of original and translated literature, textbooks, grammars, materials on the Internet etc. all of which set norms. Like French and many languages Esperanto is backed by an academy of experienced speakers. These people are deliberately selected from many different cultures. They advise on best usage. Esperanto shows no signs of dividing into dialects, but pronounciation can be audibly affected by a speaker’s first language.

Nowadays there is a wide array of activities for existing users – magazines, literature, meetings and events at home and abroad, internet activities, etc. The convenors of the U3A Esperanto group offer in the first instance support for new learners. Esperanto is usually best studied at ones own speed and in ones own time. For instance, Duolingo is a language learning website (duolingo.com) and an excellent smart phone application. Its course for Esperanto has already had more than two million learners and has stirred up a much needed awareness of the language. Duolingo is completely free to use and is specifically designed for self-study. The suggestion is that you use it for five to ten minutes a day. You can miss days, but the Duolingo system does send out reminders! Lernu.net is another extensive free website, a bit more traditional in its approach. Google Translate is a fun place to experiment. While not perfect it is surprisingly reliable. Google’s Android keyboard provides for the needs of Esperanto’s ingenious phonemic alphabet.

For those who prefer conventional textbooks there is a wide choice, but take advice. Note that offerings on Amazon can often be overpriced. The Esperanto Summer School this year is based on old well-thumbed Teach Yourself books. Not the new one just published. Esperanto may be easier to master than other languages, but difficulties do arise. We are all bound by the habits and conventions of our own first language. Inevitably these ‘get in the way’. We can also be confused when confronted by the different conventions often found in other languages, even in an easier one like Esperanto. So, what learners need is somewhere to test out their theories and discuss problems encountered. Chris and John have years of experience to share – extra materials and resources, advice on Esperanto keyboards, examples of music and videos, internet sites, easy reading, suggestions for exploiting the language practically etc. They are even ready to offer formal courses as requested, so long as participants are willing to undertake self-study.

If you want more information or support, just contact either or both.